Walter Pater’s 1885 novel Marius the Epicurean inspired Marius in Pasadena. Set in Italy and Rome during the reigns of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, the book draws a picture of the aesthetic life as Pater conceived it in late 19th-century England. It describes an Epicureanism of sympathy and human feeling that shades into the spirit of early Christianity. Pater writes:

“From that theory of life as the end of life, followed, as a practical consequence, the desirableness of refining all the instruments of inward and outward intuition, of developing all their capacities, of testing and exercising oneself in them, till one’s whole nature should become a complex medium of reception, towards the vision—the beatific vision, if one cared to make it such of our actual experience in the world.”

Marius in Pasadena is about refining perception—this “outward and inward intuition”—as Pater expresses it. The novel suggests that poetry, painting, and music offer what is best in life and that our attention to them sharpens our experience. Culture has a way of producing culture.

Describing the education of Marius, Pater writes:

“He was acquiring what it is ever the chief function of all higher education to teach—a system or art, namely, of so relieving the ideal or poetic traits, the elements of distinction, in our everyday life—of so exclusively living in them—that the unadorned remainder of it, the mere drift and débris of life, becomes as though it were not.”

It’s a simple idea. The more we experience and learn, the more affecting our sensations and thoughts become—if we attend to them while they happen.

It is this way of seeing the world that the character Marius cultivates in the novel. It puts means before ends and believes culture makes us truly human. It also reminds us that, along with Horace, we should “receive each unexpected hour with gratitude.”

A note about Pasadena.

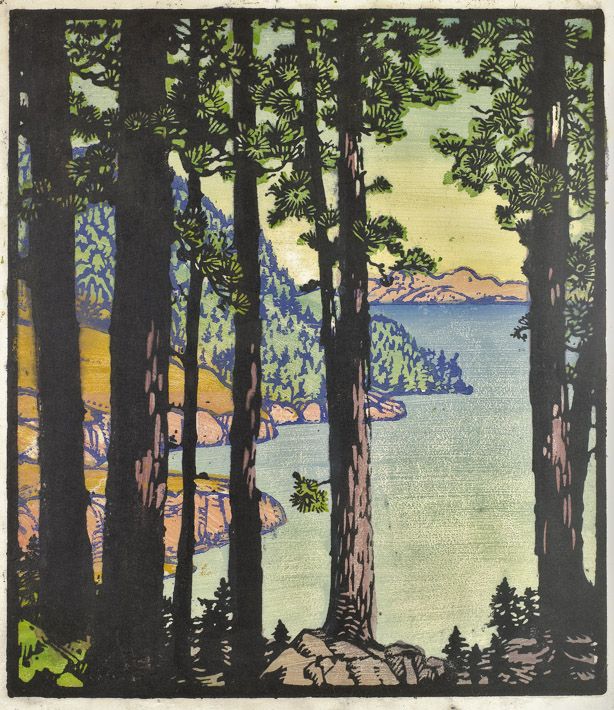

In Pasadena and its neighboring San Marino, you can get a complete aesthetic education without wandering outside their 20 square miles of dry hills and chaparral. What early Californians built as a winter resort for patrons in the East in the late 19th century has become a cultural center in the sometimes-incoherent Los Angeles. Here, we find structures built by the architects Charles and Henry Greene, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Frederick Roehrig. In its galleries, you can see paintings by Rembrandt and Giorgione, Claude and Degas, Matisse and Modigliani. It is home to Caltech, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Huntington’s extensive research library that contains millions of works from as early as the 11th century—all of this in a suburb of 140,000 souls.